The Long and Widening Road

In February 2023 I completely changed direction, moving from a reasonably well-paid self-employed job as an IT industry analyst to survival on a modest pension to embark on something far more worthwhile and meaningful. (I’m afraid I have to disagree with Stanford University scholar Roberta Katz’s research that implies the search for meaning and concern for climate change and diversity is unique to Generation Z. I'm 68.)

In February 2023, on my return from a ten-day visit to Zoho Corporation’s HQ in Chennai, India, and a visit to their rural school and farm in Tenkasi in the remote south, I've been researching the Pandora’s Box of regenerative business.

I naively anticipated a three to four-month stint doing my research and synthesizing my findings before writing about them. My goal is to add my voice to the growing clamour to regenerate our ailing planet through businesses operating on regenerative principles. Regenerative businesses, like Zoho, have discovered their souls and created enormous value for all stakeholders, including employees, customers, communities, and our planet.

My research continues. It’s never-ending. However, the strands and critical domains are beginning to emerge, drawn from many different disciplines, reflecting the complexity of the subject.

Obsidian graph view of my regenerative research

This includes awareness and education, business models, consciousness, culture, economics and finance, ecosystems-thinking, human evolution, planetary boundaries, regenerative design, and transformation approaches. The above snapshot of my rapidly expanding library of research notes gives you a sense of my web-like journey. Thank goodness for Obsidian, helping me store my notes and their connections. This will assist the upcoming synthesis and provide further food for insight.

Unlike my past research in the tech world, the latest secondary or primary sources do not always provide complete insight. The wisdom of the past is vitally relevant.

The four wise men have much to teach us

The four wise men have much to teach us

The beauty and, depending on my mood, the curse of books is the number of references cited. From such citations, I learned of three of the four: Aldo Leopold, R. Buckminster Fuller, and Lewis Mumford. Pierre Teilhard de Chardin made an impression on me in my early twenties, around 45 years ago.

Shared characteristics and a challenge to future generations

Shared characteristics and a challenge to future generations

Each, in their way, was a systems thinker. Compassion and concern for humanity and the planet were shared traits, although each has his unique perspective. All four had an acute, mixed sense of hope and foreboding toward the future.

A hope that humanity would elevate its consciousness and use intelligence and innovation for the betterment of the world. Foreboding, because of its self-centered dualistic track record culminating in new depths of cruelty and destruction in two world wars. Soon to be followed by the Great Depression, superseded by an addiction to vacuous status symbols and consumption, led by the more powerful nations in the West.

The impact on the planet and populations was less evident during their lifetimes, yet their visionary messages have never been more relevant to us. I’ll start with the eco-pioneer Aldo Leopold.

Aldo Leopold (1887–1948) — an early conservationist

Aldo Leopold (1887–1948) — an early conservationist

Aldo Leopold has been described as the ‘father’ of wildlife ecology and modern conservatism. Born in Burlington, Iowa, Leopold was a forester, conservationist, scientist, and professor of game management at the University of Wisconsin. A collection of his letters was published posthumously by Oxford University Press a week after he died, entitled A Sand County Almanac & Other Writings.

Common land misuse and theft for the benefit of the few

Common land misuse and theft for the benefit of the few

He railed against the encroachment of the countryside by what he called ‘artificialized game management.’ The increasingly popular practice: “bought fishing at the expense of another and perhaps higher recreation: it has paid dividends to one citizen out of the capital stock belonging to all.’¹

He saw the practice as extractive and a form of theft of the commons, where ‘mass-use tends to dilute the quality of organic trophies like game and fish, and to induce damage to other resources, such as non-game animals, natural vegetation, and farm crops.’²

He was alert to the accelerating encroachment of vehicle ownership and foresaw the Great Acceleration and the damage it would cause to the biosphere and the loss of solitude. “To those devoid of imagination, a blank space on the map is a useless waste; to others, the most valuable part.’’

Land Ethics

Perhaps his most significant contribution was developing what he called a land ethic.

A biological ethic is a natural limitation on all animal species’ freedom of action, which prevents them from over-exploiting resources on which all life depends. He observed that animals can only run amok when man interferes with ecological ecosystems through over-hunting predators or laying waste to habitats where they had thrived for the economic gain of the few. ‘’Civilization is not, as they often assume, the enslavement of a stable and constant earth. It is a state of mutual and interdependent cooperation between human animals, other animals, plants, and soils, which may be disrupted at any moment by the failure of any of them.’⁴

Leopold was acutely aware of the interdependence of the entire planetary ecosystem. He believed that human arrogance and ignorance are the greatest threats to the whole system. Each loss of species or soil erosion leaves humanity the poorer for it.

R. Buckminster Fuller is our next regenerative hero, who sees the world as a whole system and dislikes ’specialists.’

R. Buckminster Fuller (1895–1983) — architect, designer, inventor, whole systems behaviorist, futurist, and prolific author

R. Buckminster Fuller (1895–1983) — architect, designer, inventor, whole systems behaviorist, futurist, and prolific author

In his book, Operating Manual for Spaceship Earth (published in 1969), R. Buckminster Fuller (RBF) had an unusual take on the history of planetary colonization.

Spaceship Earth needs generalists who understand how the whole system works

Spaceship Earth needs generalists who understand how the whole system works

While historians may challenge his interpretation, the fundamental principle was that generalists trumped specialists.

He believed pirates led the colonization drive in search of riches to bring home. Successful pirates were, by nature, generalists and experts in many fields: navigation, strategy, fighting, leading, and sailing. The kings, queens, and emperors who sponsored colonization were the unwitting, useful idiots employed by the pirates. Pirate leaders used specialists for specific roles: ship carpenters, iron-mongers, horsemen, cooks, and generally those with no leadership ambitions that would ever threaten them. The specialists would also provide a useful fighting force for conquering new territories. The point of this colorful historical interpretation was to emphasize that generalists see the big picture and interdependent elements. In contrast, the narrow focus of specialists leaves them blind to the consequences of their actions on a system’s health or well-being.

Our education system works against us by producing specialists

Our education system works against us by producing specialists

He blamed the state of education that trampled on all children’s imagination and inherent creativity, sacrificing them to specialisms as they ‘progress’ through their schooling. ‘’ Specialisation is only a form of slavery wherein the ‘’expert’’ is fooled into accepting his slavery.”⁵ He believed that evolution had a greater purpose for humanity than condemning it to the life of a well-educated automaton.

Systems thinking and synergetics

Systems thinking and synergetics

Referring to Earth as a spaceship illustrates how RBF considered the planet and all its inhabitants parts of a single system. This is vital for the survival and well-being of every species and the earth itself.

“We have not been seeing our Spaceship Earth as an integrally-designed machine which to be persistently successful must be comprehended and serviced in total.”⁶

Beyond the Earth, RBF considered the solar system ’synergetic,’ feeding our planet through the ’supply-ship’ of the Sun. He coined synergetics as the science of studying systems in transformation and whole system behaviors, unpredicted by component-level behaviors. These geometric behavior patterns happened at all scales, on Earth, in the Solar System, and, throughout the Universe. These behavioral patterns required multi-disciplinary insights, so he eschewed the specialist in favor of the polymath. Solutions to tackle the complexity of climate change, biosphere and the well-being of humanity demand systems thinking, cognitive frameworks to unlock our understanding of the cause and effect of many interacting variables. As RBF noted, you cannot understand the whole system by analyzing it at the component levels, as whole system behaviors are unpredictable at that atomized level. Our education system needs urgent attention to build this thinking into the curriculum. Our collective ignorance at the systems level risks our very survival.

Economics needs an upgrade

Economics needs an upgrade

RBF noted that wealth can always be found in the event of war, yet we agonize when faced with critical ecological challenges. Yet, to paraphrase him, wealth derived from our know-how and invention can only increase with use. According to data from Macrotrends, in 1960, the World GDP was $1,384.86B, but by 2022, it had risen to $100,562.01B, an increase of over 7,000%, while according to Worldometer, the world population grew from around 3B to 8B, a rise of around 266%.

Something is clearly wrong with our use and understanding of wealth. RBF’s view was that wealth belongs to everyone but has been hoarded and unfairly exploited by the few. He proposed a form of universal income, based on what he called an R&D fellowship, where individuals can pursue any field of research and development that takes their fancy, without fear of being economically cut off. For every 100,000 fellowships, one could generate a breakthrough where everyone benefits.

“When it is realized by society that wealth is as much everybody’s as is the air and sunlight, it will no longer be rated as a personal handout for anyone to accept a high standard of living in the form of an annual research and development fellowship”.⁷

The next far-sighted gentleman and polymath is Lewis Mumford.

Lewis Mumford (1895–1990), American historian, philosopher of science and technology, sociologist, and critic

Lewis Mumford (1895–1990), American historian, philosopher of science and technology, sociologist, and critic

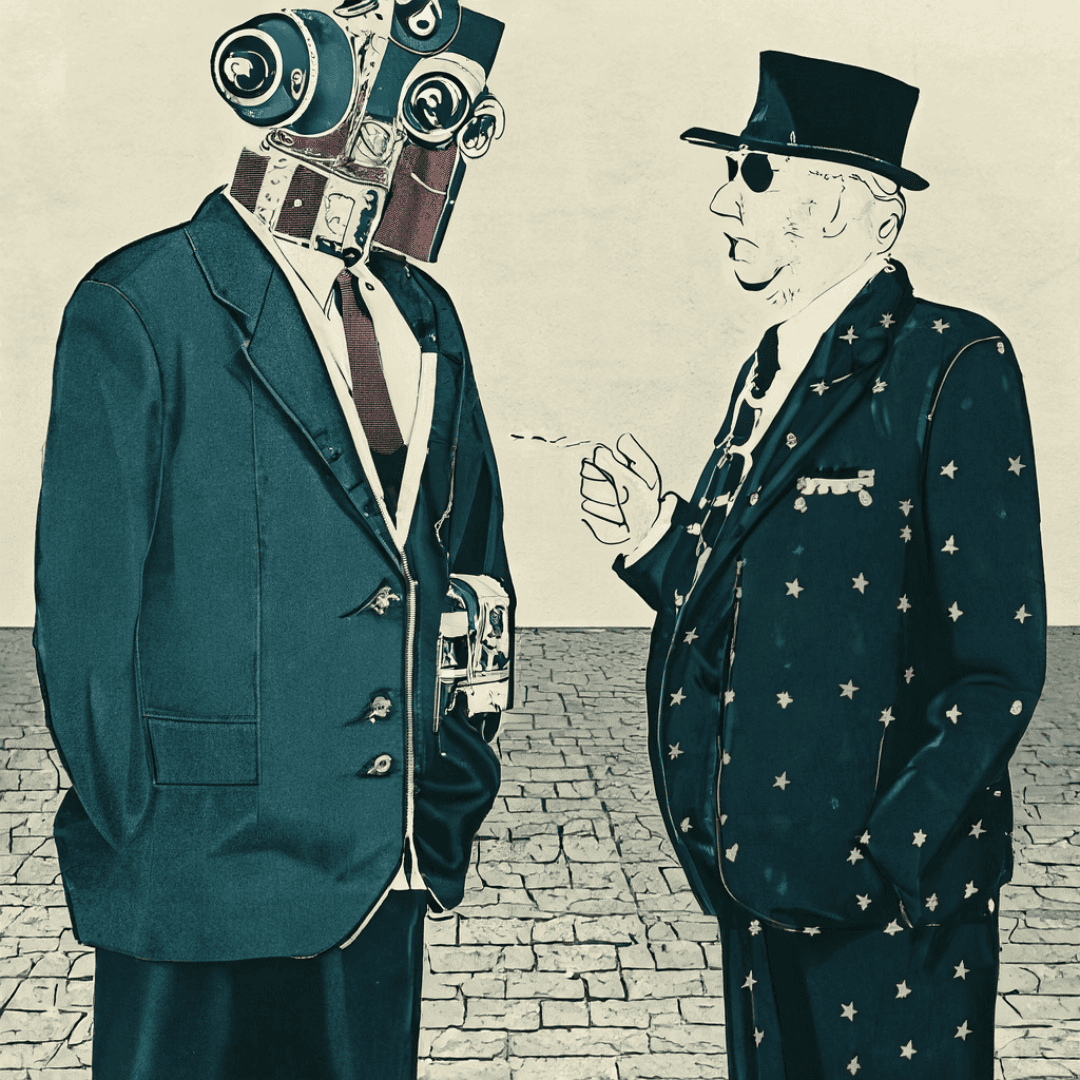

Lewis Mumford had a dystopian view of technological progress reinforced by his observations from World War II, notably the Holocaust and the efficient barbarism of the Nazi regime in Germany.

Machine vs Humanity

Machine vs Humanity

In his book The Condition of Man (1944), he noted the simultaneous rise in the machine and the moral fall of man brought about by the displacement of old-world wisdom by the rapid emergence of a utilitarian mindset. This mindset had no aspirations beyond utility and a belief in limitless growth and continuous avaricious expansion. Like a cancer of the soul it jeopardizes humanity.

“Every gain in power, every mastery of natural forces, every scientific addition to knowledge, has proved potentially dangerous because it has not been accompanied by equal gains in self-understanding and self-discipline.”⁸

( I wonder what he would have made of our current obsession with AI?)

A shift in consciousness will be the precursor to the age of ‘Equilibrium.’

A shift in consciousness will be the precursor to the age of ‘Equilibrium.’

In the forward to the book, he observed that human progress can only come following the harsh lessons of a widespread disaster: “Not once, but repeatedly in man’s history has an all-enveloping crisis provided the conditions essential to a renewal of the personality and the community. In the darkness of the present day, that memory is also a promise.’’⁹

This may have been cause for comfort after the war, but it was not a given. The seeds of the mechanistic age were sewn at the outset of the industrial age, and while working conditions had improved significantly, spiritual solace had been pushed to the margins of life and, for most, was absent in their daily lives.

He sensed the dawn of a new age of ‘Equilibrium’ struggling to emerge and that, if it came, it might take several centuries before it entirely replaced the soul-less machine age. He also warned that the transition would be painful — a battle of the soul and opposing mindsets: ‘The theme for the new period will be neither arms and man nor machines and the man: its theme will be the resurgence of life, the displacement of the mechanical by the organic, and the re-establishment of the person as the ultimate term of all human effort.- “Cultivation, humanization, cooperation, symbiosis: these are the watchwords of the new world-enveloping culture.’’¹⁰

Mumford had an acute sense of a better and fairer world trying to emerge. It will be an era where social need drives innovation, not profit. An age of regenerative business supporting the well-being of humanity.

In 2024, the emergent regenerative world is still struggling, as the general level of consciousness required has not yet been reached. The desire for conquest and brutal subjugation haunts us across the world, and the old self-centered extractive capitalism, so familiar to him, grips the reins evermore tightly.

Mumford was right. It may take centuries to evolve into a more harmonious era of equilibrium and symbiotic cooperation without national boundaries. Glaciers are melting faster while our consciousness and sense of interdependence and unity stubbornly evolve glacially.

This brings us to the scientist and Jesuit priest Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, whose lifework was spent trying to unify science and spirituality through his scientific understanding of the evolutionary process of humanity (anthropogenesis) and the cosmos (cosmogenesis). His inspirational writings were published after his death in 1955, as they were banned by the Catholic hierarchy.

Pierre Teilhard de Chardin SJ (1881–1955), renowned palaeontologist, WW1 stretcher-bearer, and Jesuit priest

Pierre Teilhard de Chardin SJ (1881–1955), renowned palaeontologist, WW1 stretcher-bearer, and Jesuit priest

It was a devout Anglican that introduced me to the writings of Teilhard de Chardin and his book, the Divine Milieu, a companion book to Le Phénomène Human ( The Phenomenon of Man), written in the 1930s. It provided an expansive and visionary view of God that struck a chord. I went to the local Jesuit seminary in Oxford and asked the duty priest why we were never taught about this at mass or at the Jesuit school I attended. His response was disappointing and patronizing. To paraphrase, the teachings were too rich for common consumption. Teilhard’s teachings had alarmed the Catholic hierarchy, and he was banned from publishing his writings. Exiled to China, he spent twenty years there as a paleontologist. He was part of the team that discovered the Peking Man, an ancestor of homo-sapiens.

Reconciling science and his Christian faith — Anthropogenesis and Complexification

Reconciling science and his Christian faith — Anthropogenesis and Complexification

Teilhard took a disciplined scientific approach to developing his theories of the evolution of humankind, building on the 20th-century science of the time. He believed that the universe and everything contained within it was in a dynamic state of becoming. He observed that since we all consist of elements created in what became known as the Big Bang (Fred Hoyle, 1949), the evolution of humans was part of the process of cosmogenesis. The potential for human existence and all lifeforms and matter was part of an ongoing process of ‘complexification.’ At every level of complexity, new wholes are formed.

The law of matter

Matter manifests in three ways: Plurality, Unity, and Energy. Individual elements attract other elements to form connections and more complex unities. Energy is the capacity for action via interaction. Thus, sub-atomic particles form atoms, which attract other atoms to form molecules. These attract other molecules to form even more complex compounds. This process of complexification through energy and attraction continues to form evermore complex and higher-level unities, including stars, planets, moons, lifeforms, including us.

Teilhard stated that physics is the science of space and clock time, whereas anthropogenesis is a science of space and process time.¹¹

Tangential and radial energy

Teilhard identified two forms of energy: tangential, which, once consumed, is exhausted, such as spent fuel. The second is radial or divine energy and love, the pull of the future, which drives elements toward unions of ever greater complexity. ‘’Tangential energy dissipates with use, while radial energy continually increases with use, as Complexity and Consciousness continue to increase.”¹²

Eventually, at the Omega Point, all tangential energy has been dissipated, and what remains is a super-abundance of radial energy in the form of spirit. God, fully revealed.

Teilhard the systems-thinker

Teilhard the systems-thinker

However, to understand the process of anthropogenesis and cosmogenesis, like R. Buckminster Fuller, Teilhard noted that the traditional scientific reductionist approach isn’t appropriate for understanding complete and increasingly complex systems: ‘’we need to take the perspective of looking at Earth as a single system and focus on how everything is interacting and working together. This is the viewpoint of geogenesis, the evolutionary ‘’becoming’’ of Earth, and cosmogenesis, the ‘’becoming of the universe (cosmos) itself.”¹³

The within and without of things and the emergence of consciousness

The within and without of things and the emergence of consciousness

Everything has a ‘within’ and a ‘without.’ What we see, the physical, is the without. The within, in humans, is the inner life of feelings, emotions, dreams, thoughts, and love. Even the smallest particle has a within, its energy and potential to attract and combine in higher level wholes. According to Teilhard, consciousness is a function of the level of complexity reached. The within matches the capabilities generated by the without. ‘’ By the law of evolution, the universe is destined to become ever-more conscious of itself, thereby revealing what its true nature is and always has been from its first moments — psychic, that is, mental and spiritual.”¹⁴

He believes that the story of the universe and everything in it is in transition, gradually converging on its highest state (possibly billions of years to come), the Omega point. God’s evolutionary project is the evolution of consciousness powered by His love’s radial (unseen) energy.

Stewards of creation with a responsibility for the whole

Stewards of creation with a responsibility for the whole

Rather than be passive passengers on this journey toward Omega, Teilhard calls us to become active participants. To get to the next level of consciousness as a species, we need to evolve as a new unified whole, recognizing our interdependence and caring for each other and the planet. Judging by what is happening in the world today in 2024, we have a long way to go.

The Noosphere and humanity’s next evolutionary stage

The Noosphere and humanity’s next evolutionary stage

Teilhard’s theory of increasing complexity led him to consider what was next for humanity. While not completely covered in this article, his systems view of the human phenomenon was that humanity was intimately connected to life in all its forms. The individual separateness experienced by most of us was an illusion based on our limited consciousness. His non-dualistic perspective, reflected in his ‘law of matter,’ enabled him to envisage the next stage in humanity’s evolution — a collective wholeness and unity.

Rather than focus on personal spiritual development, he encouraged us to seek a collective spiritual consciousness, the Noosphere, as he called it. That would create higher energy levels to power our evolution toward the Omega Point. He envisaged that this might take millennia to evolve. “The day will come when, after harnessing space, the winds, the tides, and gravitation, we shall harness for God the energies of love. And on that day, for the second time in the history of the world, we shall have discovered fire.”¹⁵

Today, we might think of the internet as a rudimentary, Wild West form of the noosphere. But, in centuries to come (if we survive this one), it may become a psychic web, enabling us to connect and interact and, through the radial energy generated, empower us to create heaven on earth.

So what have we learned from these four wise men that can help us navigate toward a regenerative future?

So what have we learned from these four wise men that can help us navigate toward a regenerative future?

Four common and interdependent themes emerge:

- A higher level of consciousness is required

- Cooperation and unitiy recognition of our interdependence and relationship with the planet and its biosphere is an essential component in that higher consciousness

- Systems thinking - seeking to understand the whole rather than reductive analysis and assumption

- An urgent need, yet to be fulfilled for new economic thinking to oil the wheels.

A higher level of consciousness

A higher level of consciousness

Aldo Leopold gave us the biological ethic to work with nature, not exploit it. R. Buckminster Fuller encouraged us to turn away from the slavery of expertise and to broaden our education to understand how everything is connected and interdependent. Lewis Mumford articulated an emerging era of cooperation, cultivation, and symbiosis, where machines serve social purposes and don’t turn us into passive automatons. Teilhard de Chardin explicitly stated that we are on a journey to a higher level of consciousness and provided hope that we can achieve it by loving the world and all humanity.

Cooperation and unity

Cooperation and unity

Each of the four demanded cooperation as an essential element of positive action — a prerequisite for a regenerative future and global unity. A recognition of our interdependence and relationship with the planet and its biosphere is an essential component in that higher consciousness

Systems thinking

To create a regenerative future, we need to think in terms of wholes, not parts. As an ecologist, Aldo Leopold desperately wanted people, especially those with economic power, to understand the impact of their extractive behavior on all wildlife. To recognize the connectedness of the soil, plants, and animals and to understand the consequences of destroying ecosystems. R. Buckminster Fuller railed against the specialists who failed to understand the whole system. Lewis Mumford sensed that we were on the cusp of a new era that depended on cooperation to improve the lives of all.

Pierre Teilhard de Chardin was perhaps the ultimate systems thinker, seeing the evolutionary patterns of the universe and humanity.

New economic thinking to remove barriers

New economic thinking to remove barriers

Of the four, R. Buckminster Fuller was the most explicit, promoting the concept of R&D Fellowships, emancipating those whose jobs may disappear to focus on pushing the boundaries, solving problems and challenges, and adding to humanity’s innovation inventory.

Fortunately, many decades later, new economic thinkers are gradually gaining traction to help the regenerative movement and support our innate calling to generate well-being for all. And there are increasing numbers of regenerative businesses emerging which, despite all the dreadful news we see today, offer hope for tomorrow. I look forward to exploring some of these in the coming weeks and months.

Footnotes

- Aldo Leopold: A Sand County Almanac & Other Writings on Conservation and Ecology (LOA #238) (Library of America) (p.147). Library of America. Kindle Edition.

- ibid (p.147)

- ibid (p.151)

- ibid (pp.326–327)

- Fuller, Buckminster. Operating Manual for Spaceship Earth (p 59). The Estate of R. Buckminster Fuller. Kindle Edition.

- ibid (p.59)

- ibid (p.136)

- Lewis Mumford lewismumfordConditionMan1944 — Book Source: Digital Library of India Item 2015.188937 (p.393)

- ibid (p.6)

- ibid (p.399)

- Savary, Louis M.. Teilhard de Chardin’s Phenomenon of Man Explained (p. 69) Pauli’s Press. Kindle Edition.

- ibid (p.76)

- ibid (p.63)

- ibid (p.98)

- “The Evolution of Chastity,” in Toward the Future, 1936, XI, 86–87)